- Blog

- Tackling the Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis: An Integrated, Whole-of-Society Response

Tackling the Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis: An Integrated, Whole-of-Society Response

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified many of the risks typically linked to poor mental health – such as financial insecurity, job loss, and fear – while at the same time, many protective factors have sharply declined. These include social interaction, stable employment, access to education, opportunities for physical activity, consistent daily routines, and availability of healthcare services. As a result, there has been a serious and unprecedented decline in mental well-being across populations.

In nearly all countries, people without jobs or those facing financial stress have reported worse mental health than the general public. This pattern existed before the pandemic but has worsened in some cases. In response, OECD countries have made strong efforts to expand mental health services and introduced policies to safeguard incomes and jobs, helping to ease some of the psychological burden.

Still, the widespread mental strain brought on by the pandemic calls for a more coordinated and society-wide approach to mental health care – one that goes beyond emergency support to prevent long-lasting harm.

Key Findings

The pandemic had a major negative impact on the population's mental health:

- Starting in March 2020, rates of anxiety and depression rose sharply, and in some countries, they even doubled. The highest levels of distress often matched times when COVID-19 deaths surged, and strict lockdowns were in place.

- In all countries, people without jobs or facing financial hardship reported worse mental health than the general public. This issue existed before the pandemic but appears to have gotten worse in some situations.

- Mental health systems were already under pressure before 2020. The large increase in mental health needs since the pandemic began calls for a level of support that goes far beyond what was previously available. OECD countries have responded quickly to increase mental health care:

- Most introduced new mental health hotlines or online resources to offer coping advice during the crisis. Many also expanded access to mental health services or raised funding.

- A number of OECD countries acted fast to protect jobs and incomes while also helping people adjust to working from home. Job retention programs played a key role in supporting workers' income and emotional well-being.

- Before the pandemic, mental health was only weakly connected to social welfare, employment, and youth policies. There is now an urgent need for more connected and long-term strategies. A full society-wide approach to mental health means:

- Ensuring continued access to mental health care, whether in person or through telehealth, must be a top priority. Expanding access to proven mental health services is critical, especially alternatives to school- or work-based programs that were disrupted.

- Employers should take active steps to support workers’ mental health, including those who were on furlough or similar job schemes.

- Policymakers need to address the mental health effects of long-term remote work and consider expanding support for job seekers through public employment services.

Technical Note on Language and Data

This brief uses the terms “mental health conditions” and “mental health issues” rather than “mental illness” or “mental disorder.” This choice reflects a shift in language aimed at reducing stigma, raising awareness, and promoting a person-centered, recovery-focused approach. The goal is to use words that highlight individual strengths and experiences, acknowledging that mental health challenges vary from person to person.

There are still major gaps in data on mental health, especially when broken down by age group. This brief mainly relies on the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms, collected through surveys, as a stand-in for broader mental health status. When available, surveys that use validated tools – such as the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale for anxiety and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression – are included. However, the survey samples, especially those gathered quickly during the COVID-19 crisis, are not always representative. In addition, survey methods vary by study, which makes comparing countries difficult. Since symptoms are self-reported, rising rates may also be influenced by greater awareness or changing levels of stigma, which can affect trends across countries and over time.

Population Mental Health Has Deteriorated Significantly Since the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic

For many years, the overall rate of mental health conditions remained relatively steady. However, this pattern changed in 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic began. Starting in March 2020, cases of anxiety and depression rose sharply. In countries like Belgium, France, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, anxiety levels in early 2020 were at least twice as high as in previous years. Similarly, depression rates doubled or more in countries including Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, the Czech Republic, Mexico, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In 2020, key risk factors for poor mental health – such as job loss, financial pressure, and fear – became more widespread. At the same time, protective factors like social interaction, stable work or school routines, access to exercise, daily structure, and healthcare access all dropped.

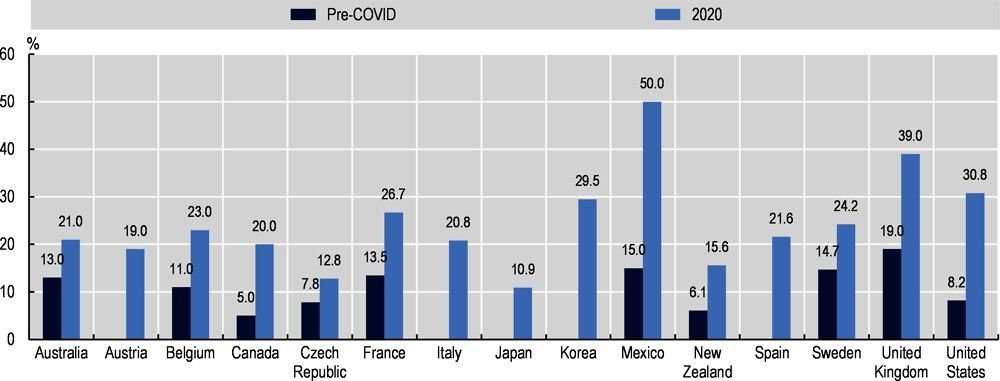

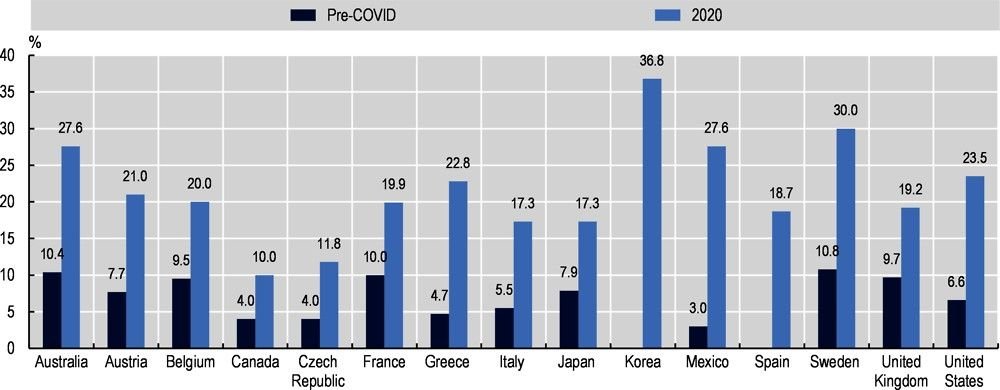

When compared with pre-pandemic data, the increase in anxiety and depression throughout 2020 is clear. Although different OECD countries used various survey tools to measure mental health symptoms, and some surveys were not fully representative of national populations, the trend is consistent. Despite these differences, the overall rise in anxiety and depression across countries is both clear and significant.

Increase in Anxiety Symptoms During Early 2020

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms rose sharply across many countries. In Mexico, rates reached 50%, while Korea and the United Kingdom also saw high levels at 29.5% and 39% respectively. Other countries experienced notable increases, including the United States (30.8%), France (26.7%), Italy (20.8%), and Australia (21%). Even countries with lower pre-pandemic levels, such as Canada and the Czech Republic, saw a doubling or more in anxiety prevalence. These figures reflect a widespread deterioration in mental well-being triggered by the pandemic’s onset, though differences in survey methods and reporting standards affect direct comparisons across nations.

Sharp Rise in Depression Rates During Early 2020

In early 2020, symptoms of depression increased substantially across multiple countries. Korea reported the highest prevalence at 36.8%, followed by Sweden (30.0%), Australia (27.6%), and Mexico (27.6%). Other nations also experienced marked increases, including Greece (22.8%), Austria (21.0%), Belgium (20.0%), the United States (23.5%), and France (19.9%). Even in countries with previously low rates, such as Canada, the Czech Republic, and Japan, depression levels rose noticeably. This widespread increase highlights the mental health toll of the pandemic, although variations in survey tools and sample representativeness mean that comparisons between countries should be approached with caution.

Population Mental Distress Was Highest During Periods of Intensifying COVID-19 Deaths and Measures to Limit Transmission of the Virus

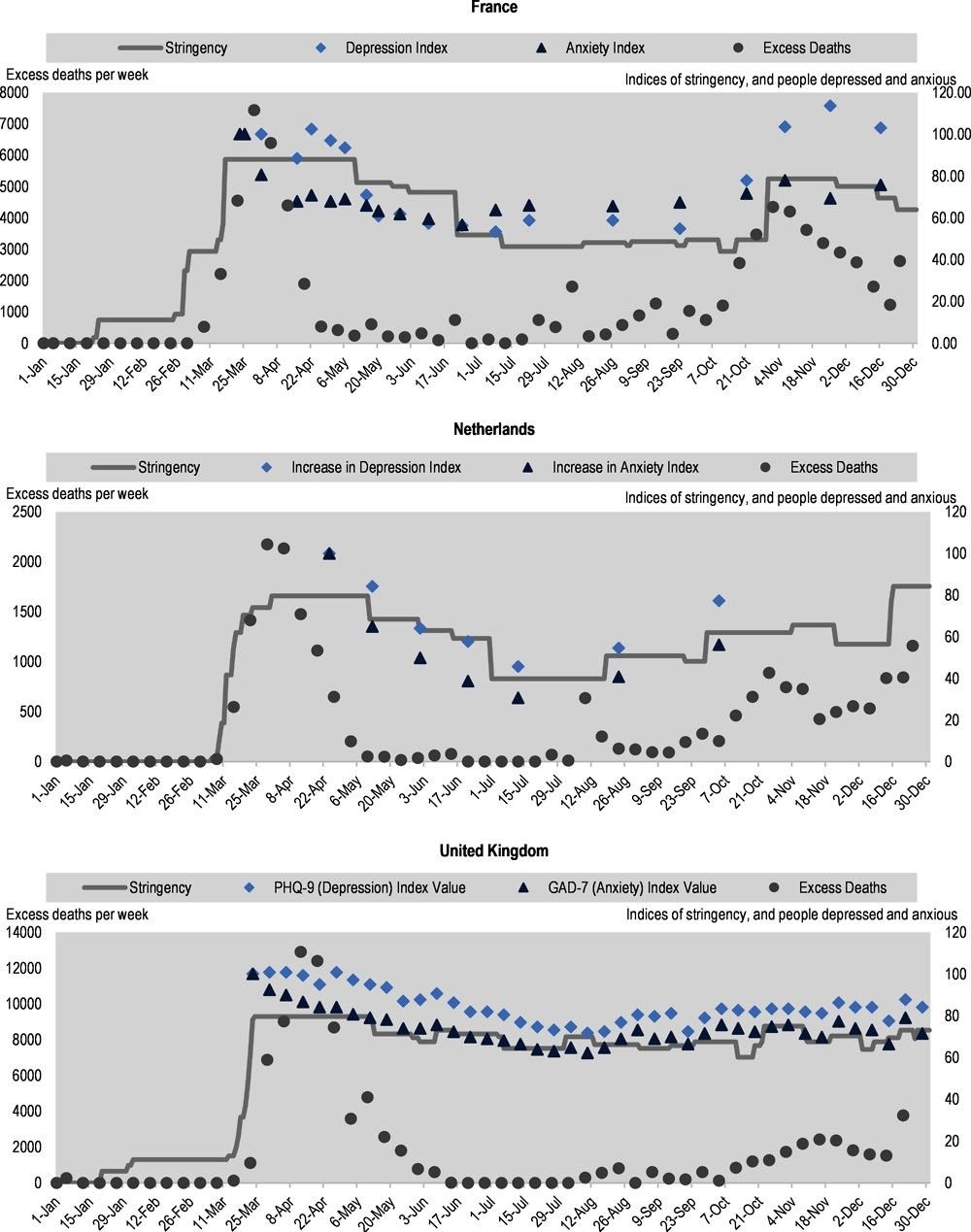

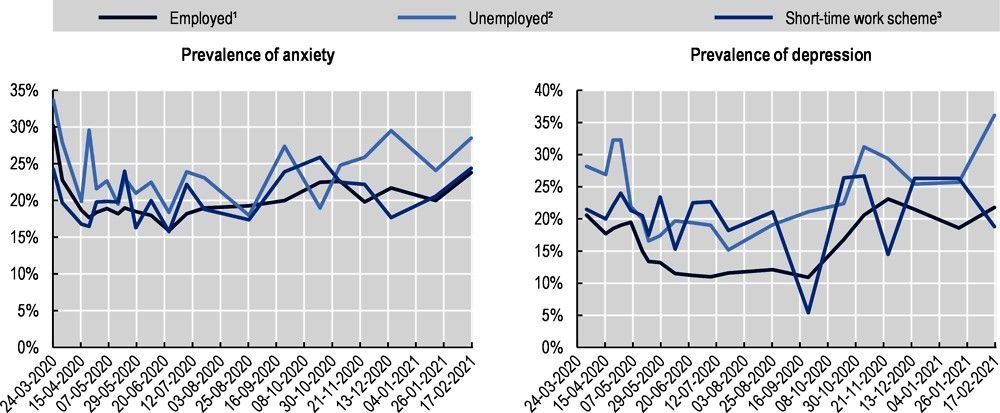

Throughout 2020 and into 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in several waves of rising cases, hospitalizations, deaths, and public health restrictions. Mental health trends followed a similar wave pattern, with mental distress peaking during times of high death rates and when strict measures were in place to slow the virus’s spread. The first major spike in distress occurred in March – April 2020, easing slightly over the summer months as cases dropped and lockdowns were lifted in parts of Europe.

In countries that regularly tracked population mental health – such as Canada, France, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States – levels of anxiety and depression were highest from mid-March to early April 2020. These levels dropped around June – July then began rising again from September onwards. Most countries showed similar mental health patterns, which aligned with both the severity of pandemic policies (measured by Oxford University’s Blavatnik Stringency and Policy Index) and excess death rates. This pattern is seen clearly in the mental health trends from France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.

Timely survey data collected during the pandemic provided nearly real-time insights into mental health – a level of detail not available during earlier crises like the 2008 financial downturn. As the pandemic continues, and even as the immediate health emergency eases, it remains crucial to monitor mental health closely. This will help determine whether mental health levels return to their pre-pandemic average or whether elevated rates become the new normal. If the latter proves true, the policy implications will be significant.

People With Less Secure Employment, Lower Educational Status, And Lower Income are Experiencing Higher Rates of Mental Distress During the COVID-19 Crisis

The likelihood of experiencing poor mental health during the pandemic has differed across population groups, with factors like age, gender, job security, financial stability, and education level playing key roles. Young adults, people living alone, those with fewer financial resources, and the unemployed have reported higher levels of mental distress. On the other hand, individuals who kept working during lockdowns – especially those working from home – were generally less likely to report symptoms of anxiety and depression, at least during the early months of the crisis.

Not being employed during 2020 was linked to greater mental health challenges. Long-term data shows that people with jobs were less likely to report depression or anxiety than those without work. Many OECD countries introduced or adjusted job retention and short-time work schemes to help protect employment. These programs allowed workers to keep their contracts even when their jobs were paused. French data suggests that these programs helped lessen the mental health toll of the crisis. In the United Kingdom, similar findings emerged – people in unstable jobs who were furloughed did not report a rise in mental distress, while those in similar roles who were not furloughed experienced a significant increase.

Lower Socio-Economic Status (SES) Has Long Been Associated With an Increased Risk of Poor Mental Health

People with lower socio-economic status have consistently faced a higher risk of mental health problems, and this trend has continued during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United Kingdom, anxiety was tracked over a 20-week period starting from the first lockdown in March 2020. During this time, individuals with lower levels of education or income reported consistently higher anxiety scores. Another UK-based study found that people who lost income and became reliant on government support – like universal credit or self-employment grants – or who faced long-term financial stress saw their mental health decline more than the average during April 2020.

Still, the relationship between socioeconomic status and changing mental health during the pandemic has not been the same in every country. In the United States, for example, an April 2020 survey found that people with higher income and education reported a bigger drop in life satisfaction and a larger rise in depressive symptoms than lower SES groups when compared to data from 2019.

The Prevalence of Mental Health Conditions Is Also Known to Differ Between Men and Women

Women are more likely than men to report symptoms of depression or anxiety, and this gap widened during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the UK, working parents experienced more mental strain during the first wave of the pandemic than those without children, and this was especially true for working mothers. In the United States, data from March to April 2020 showed the gender gap in mental health grew by 66%.

Delivering an Integrated Whole-of-Society Policy Response to Support Mental Health During and After the COVID-19 Crisis

To properly address the mental health effects of the pandemic, policies must be integrated across sectors. The OECD Recommendation on Integrated Mental Health, Skills and Work Policy – which all OECD countries agreed to in 2015 – calls for this type of cross-cutting approach. This recommendation is based on years of OECD research and promotes early support in schools, the workplace, and welfare systems to improve outcomes for people facing mental health issues. Now more than ever, early detection and joined-up services are essential. Alongside wider public campaigns, such policies can also help reduce mental health stigma and encourage healthier environments in schools and workplaces.

Safeguarding Access to Mental Health Services and Responding to the Increased Need for Mental Health Care

The COVID-19 pandemic caused major disruptions in mental health service delivery. A WHO survey from the second quarter of 2020 revealed that over 60% of countries experienced interruptions in mental health services: 67% reported disruptions to counseling and therapy, 65% to harm reduction services, and 35% to emergency care. OECD countries saw similar patterns. In Italy, by early April 2020, 14% of community mental health centers had closed, 25% had reduced hours, and around 78% of day hospitals were shut down. Roughly 75% of non-urgent care was shifted to remote formats, mainly by phone. In the Netherlands, during the first pandemic wave, referrals to mental health services fell by 25–80%, treatment demand dropped by 10–40%, billable hours declined 5–20%, and bed occupancy dropped by 9%.

In response, mental health care providers rapidly turned to digital delivery, especially telehealth. By mid-2020, more than 80% of high-income countries told the WHO they were using telemedicine, online therapy, or mental health helplines to replace in-person appointments. In the United States, temporary changes to federal regulations allowed telehealth across state lines and on non-secure platforms. By the end of 2020, Kaiser Permanente – serving 12 million people – was providing 90% of psychiatric care virtually. In Canada, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health increased virtual visits by 750%, from around 350 to 3,000 between March and April 2020.

Early feedback has been positive. Clients and clinicians have both reported satisfaction with video-based care, good adherence to treatment, and more frequent contact in some cases. In Australia, telehealth use surged: by the end of April 2020, half of all mental health services under the Medicare Benefits Schedule were being delivered remotely. Even as in-person services resumed later that year, nearly 100,000 telehealth appointments were still happening weekly – compared to none in March. In England, mental health services moved significantly to phone and video by April 2020, with in-person visits falling below 2019 levels.

The use of other digital mental health tools also rose. In the United States, Talkspace, an online therapy platform, saw a 65% increase in users between mid-February and the end of April 2020. A federal emotional distress hotline reported a 1,000% surge in calls in April 2020 compared to the same time in 2019. Self-screening tools on Mental Health America’s website were used 60–70% more often during the pandemic.

Governments also launched new digital resources. In April 2020, Canada rolled out Wellness Together Canada, a free online portal offering self-assessments, wellness tools, and text or phone counseling. Additional funding was provided to services like the Canada Suicide Prevention Service and Kids Help Phone. Canada also included self-care features in the COVID-19 symptom-tracking app to support mental health during the outbreak.

OECD Countries Must Now Increase the Availability of Mental Health Services and Respond to the Increasing Demand for Care

Although countries have acted to address growing mental health needs, services were already under pressure before the pandemic began. In some places, the COVID-19 crisis has widened the gap between demand and access. For instance, in August 2020, 9.2% of U.S. adults said they needed counseling or therapy in the past four weeks but didn’t receive it. In 2019, just 4.3% said they couldn’t access care over the course of a full year due to cost.

Most OECD countries have introduced at least some new measures to support mental health. These include expanding access to online information, launching new mental health phone lines, switching services to telehealth formats, and in some cases, boosting service capacity or public funding. In Portugal, a free 24-hour helpline was set up, staffed by 63 psychologists. This initiative was developed by the Ministry of Health, supported by the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (which contributed EUR 300 million), and backed by the Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses.

Many countries have shifted some services to digital or phone-based formats and, in some cases, expanded access or benefits. In Australia, the number of reimbursable psychological sessions under the Medicare Benefits Scheme was doubled from 10 to 20. The government also allocated funding to extend telehealth services, allowing all Australians to access care through phone or video from home. In France, concern over university students’ mental health led to the creation of the ‘Chèque psy étudiant’ in February 2021, offering three free consultations with a psychologist or psychiatrist.

Some governments have committed to additional mental health funding in response to the pandemic’s impact. In Australia, AUD 5.7 billion was allocated for mental health and aged care as part of its COVID-19 response plan. Canada invested CAD 11.5 million in projects targeting the mental health of vulnerable groups. Ireland’s 2021 budget included EUR 38 million for new mental health initiatives and another EUR 12 million for existing services – EUR 50 million more than in 2020. Latvia allocated EUR 7.12 million in 2021 to mental health, covering funding for specialists, general practitioners offering mental health support, and emotional assistance for healthcare workers. Chile, in February 2021, announced a 310% increase in its mental health budget compared to the previous year.

Adapting Workplace Policies to Promote Mental Health Amidst the COVID-19 Crisis and Beyond

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people have lost their jobs, and many others have faced major changes in how they work. Some workers remain on job retention programs and may have been out of work for extended periods. Essential workers have continued working in person, often with a higher risk of exposure to the virus and new workplace safety measures. Others have shifted abruptly to remote work, sometimes for months at a time.

Teleworking Poses New Challenges for the Relationship Between Work and Mental Health, and All Employers Could Do More to Support Workers’ Mental Health

The pandemic brought a sharp rise in teleworking. At the start of the crisis, about 39% of workers in OECD countries moved to remote work. Research from before the pandemic on how telework affects mental health is limited and mixed. While remote work can offer flexibility, it can also blur the line between home and work life, increase working hours, and create feelings of isolation – factors that may harm mental well-being.

Even before COVID-19, remote employees in most OECD countries worked longer hours than their office-based peers. This trend continued during the pandemic. A global Ipsos survey from late 2020 found that 44% of respondents across 28 countries (including 20 OECD countries) said they were working irregular hours due to the pandemic. Video meetings may also be more exhausting than in-person ones, and the merging of work and personal life has negatively affected sleep quality. Teleworking is likely to remain common. In mid-2020, 78% of employees surveyed in the EU-27 said they wanted to work from home occasionally after restrictions ended. In Japan, 79% of employees said they would prefer to continue teleworking at least some of the time. These new ways of working call for updated protections to safeguard mental health. In response to work-life balance concerns, the European Parliament pushed in December 2020 for a legal “right to disconnect” outside working hours. France, Spain, Italy, and Luxembourg already have similar laws.

With increased mental health risks during the pandemic, employers can play a bigger role in supporting workers – both in person and remotely. Many employees still feel that their workplaces are not doing enough. A PwC survey of U.S. remote workers found that employees were 26 percentage points less likely than executives to say their organization was doing well in supporting mental health. Large companies in the U.S. are expanding access to virtual mental health care, but small and mid-sized businesses may struggle to provide the same level of support.

Whole-of-Workplace Initiatives Can Also Help Ensure Work Contributes to Better Mental Health

One helpful framework is Canada’s National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace, introduced in 2013 by the National Mental Health Commission. It offers voluntary guidelines for building mentally supportive workplaces. A key element is mental health training for managers, which governments can promote through awareness efforts. A 2017 Deloitte study in the UK found that while about half of managers saw value in mental health training, less than 25% had actually received it. Better management practices can encourage open conversations, prevent conflict – an important trigger for mental health issues – and help identify problems early.

Design Job Retention Schemes to Promote the Mental Health of Workers

The pandemic has also transformed the job landscape, with many countries relying on job retention programs to protect workers. These schemes supported more than 60 million jobs across the OECD or roughly 20% of dependent employment. While they helped shield workers’ mental health early on, the effects of being furloughed or on reduced hours for long periods are less understood.

Evidence from the UK and EU shows that even eight hours of work per week can provide most of the mental health benefits of full employment. To support mental health, governments could encourage employers to reduce hours rather than stop work completely and update job retention policies to allow part-time work. Before the pandemic, 23 OECD countries already had short-time work programs like Germany’s Kurzarbeit and Japan’s Employment Adjustment Subsidy. Many expanded these programs during the crisis. Initially, new job retention schemes in the OECD (except Iceland’s) only applied when hours dropped to zero, but both the UK and Denmark later revised their programs to allow compensation for partial reductions in working hours.

Addressing Poor Mental Health Through Strengthening Public Employment Services

Job loss and unemployment are key risk factors for declining mental health. Across the OECD, the number of unemployed people has grown by around 10 million compared to pre-crisis levels, with the hardest-hit sectors being leisure, hospitality, transport, and retail. This issue is not just temporary – unemployment is expected to remain above pre-pandemic levels at least through 2022.

Helping people return to work through job-search support, career counseling, and training remains a vital way to improve mental health among working-age adults. Preventing long-term unemployment is especially important, as people who are out of work for extended periods often become disconnected from the labor market. This is particularly concerning for young people and recent graduates. During the global financial crisis, many countries cut back on employment services even as joblessness rose, leading to a 21% drop in time spent per client. While countries now face pressure to scale back some employment services due to rising demand, one area that must not be cut is mental health support. Even before the pandemic, employment services provided limited access to mental health care for those who needed it.

With more people now facing mental health challenges and continued uncertainty in the job market, it's more important than ever to expand – not reduce – combined mental health and employment services.

Providing support for mental health alongside job services is essential. Studies show that mental health care alone does not lead to better employment outcomes for people with mental health conditions. In contrast, programs that integrate mental health support with job services have been proven effective. However, large-scale implementation of these programs is still rare in most OECD countries, and existing efforts mainly target individuals with more severe conditions.

Active labor market programs can also ease the mental health impact of unemployment. Research from the UK found that those enrolled in these programs reported better mental health than other unemployed people, though still not as good as those with jobs. These programs offer structure, a sense of routine, social interaction, and opportunities to build or maintain networks – benefits similar to being employed. While helping people get back to work should remain the core aim of these policies, their effect on mental health should also be considered when measuring success.

Mary Watson

Mary Watson